4 Key Questions States Should Ask About College- and Career-Readiness

States Need Credible Evidence in Their Assessment and Accountability Systems

State policymakers and educators who aim to help high school students be college- and/or career-ready should prepare to catch two waves spreading through education. One is rising in high schools; the other in colleges. Both demand that states change their content standards, assessments, and assessment practices.

Two documents illustrate these waves. At the high school level, the Ohio Department of Education’s Strategic Plan showcases the broader view of essential competencies that are already being instituted by many states and districts that use a “portrait of a graduate” approach. At the college level, the University of Alaska’s course catalog provides a window into how colleges are using more focused career-anchored competencies to provide students with credentials and certificates that have credence and currency in the job market.

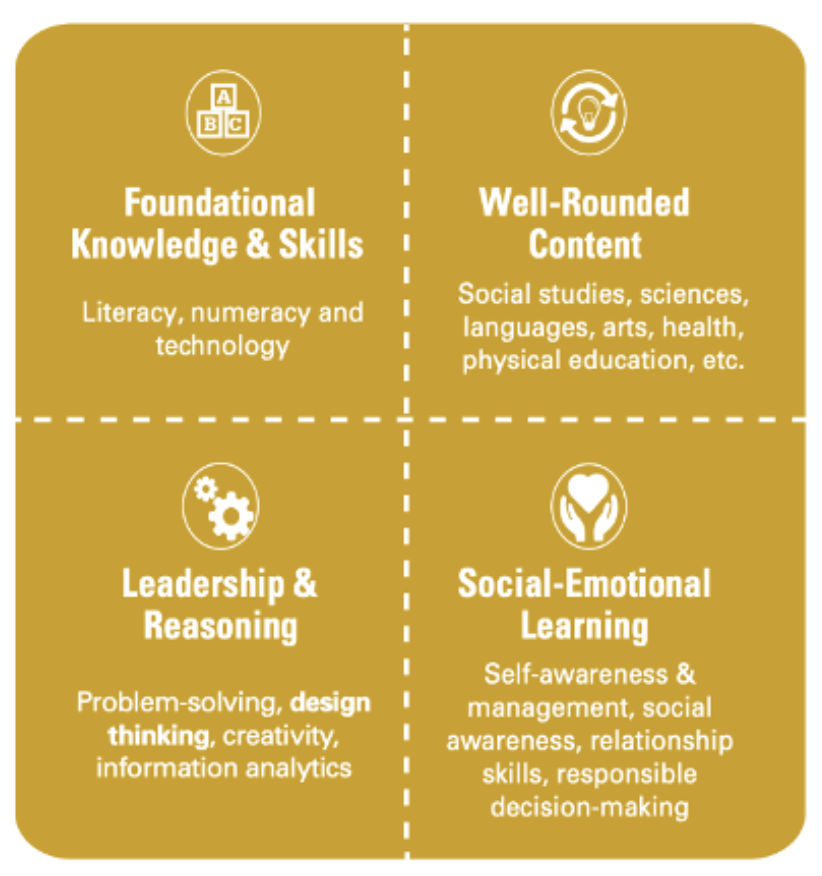

The Ohio document identifies the content and skills the state considers required to “challenge, prepare and empower students for success beyond high school by giving them tools to become resilient, lifelong learners.” In its “four equal learning domains,” Ohio identifies skills and knowledge well beyond the English language arts/reading, mathematics, and science mandated in current federal assessment systems. Ohio also identifies a range of “21st-century” leadership, reasoning, and social-emotional learning skills. Several states have generated similar descriptions for their “portrait of a graduate” frameworks. All include some type of 21st-century skills beyond academic content knowledge and skills, none of which are currently included in any state’s federal assessment or accountability system.

The University of Alaska course catalog lists more than 95 occupational endorsement certificates and associate degrees explicitly designed to qualify someone to be job-ready—without a bachelor’s degree—in diverse, specialized areas such as air traffic control, applied behavior analysis, and construction management. Many of these programs include or explicitly prepare students to take industry certification programs. These college programs reflect the use by many employers of hundreds of specialization certifications for hiring, assignment, and promotion.

A corollary of this specialization is that there is no single body of content knowledge—Algebra II, for instance—that all students must learn to be college- or career-ready. It is also clear that many college students value obtaining the evidence of specialized skills that employers value.

Key Questions to Ask About Assessment and Accountability Systems

States and districts will need to respond to several challenges to fully take advantage of these two waves.

How General or Specific?

States’ portraits of a graduate identify broad skills without specific contexts; the job-related courses and certificates are quite specific. There are compelling arguments for foundational knowledge and skills that may be applied across specific jobs and will be more “future-proof.” Arguments may also be made for preparation that is demonstrably relevant and ready right away.

Most states with an accountability “postsecondary readiness” indicator include both general and specific college- and career-ready measures. This is easily done when they are optional. States’ ELA/reading and mathematics proficiency requirements are general, yet do not address the 21st-century competencies in portraits of a graduate. States and districts will need to amend their content standards and learning targets to incorporate traditional academic content knowledge and skills, 21st-century skills, and more specific college- and career- knowledge and skills. They will need new assessments that credibly measure the expanded set of competencies that are both more general and more specific than what is assessed now.

How Common or Individualized?

Most state assessments are predicated upon common, near-universal content standards that apply to every student. For the past 30-plus years, states have been required to assess all students on—and hold all schools accountable for—students having the same basic opportunities to learn. But both waves emphasize individual choice and applications. Different pathways among students and highly specific job or course requirements imply there may be far less content or skills in common.

States and districts will need to define what and how much should be required for each student, and why. States that want to support more individualized evidence will need to create ways to accommodate it within assessment and accountability structures that have assumed and valued strict comparability.

What degree of “readiness”?

It is clear there are sequential degrees of evidence of readiness for college: satisfying high school graduation requirements, achieving a score on a college entrance exam that’s likely to be accepted for credit, earning college credit while in high school through dual credit work, and actually enrolling (and succeeding) in college. Similar degrees of readiness have evolved for jobs or careers.

States and districts will need to clearly define what degree of readiness they are requiring and what they are offering or supporting. They will also need to identify what evidence of readiness they will accept. Both states and districts should ensure their program offerings are equitable and effective.

What competency evidence “counts,” and for whom?

It is clearer than ever that colleges and employers want evidence of student competence, and that students value having credible credentials or other means of signaling their competence. Colleges are wrestling with whether their degrees carry enough credence and value in the workplace, so many are moving to ensure that graduates also earn—or are prepared to immediately earn—industry-recognized credentials.

Perhaps to a greater degree, states and districts should be working to ensure that the state/district requirements for demonstrated competency—high school diploma, proficiency in meeting state knowledge/skill standards, state postsecondary accountability measures—also are accepted as credible by post-secondary institutions and provide a currency that opens doors for students.

Only rarely have student proficiency scores on state assessments—the foundation for states’ student and school accountability systems—counted for anything in the postsecondary world of “enrolled, employed, or enlisted.” Surely it would be well worth the effort—by K-12 education, higher ed, business, and government working together—to create more coherence in what evidence counts as competency across K-12 and post-secondary users.

As states and districts think about how they can help their students graduate college- and/or career-ready, it is especially important that they (re)consider the kinds of evidence they will help their students provide that will be credible and useful after the students leave high school. They’ll need to address these four questions:

- How should content standards and assessments appropriately incorporate both more general and more specific college- and/or career-readiness knowledge and skills?

- What knowledge and skills should be common to all students, and what should be individualized? How can more individualized assessments be incorporated for accountability and other data aggregations?

- What degree(s) of college- and/or career-readiness will be sought after and supported?

- What competency evidence will count, and for whom?

States and their partners should work to reflect and direct the educational waves of the future. Those who tackle the challenges to develop more relevant learning targets, more valid assessments, and more credible outcomes that are useful to students, colleges, and employers, will not only empower their graduates, but will make state and district standards, curriculum, assessment, and accountability more powerfully relevant than they have been for generations.