Culturally Sensitive, Relevant, Responsive, and Sustaining Assessment

Are There Limits to Making Large-Scale Standardized Testing Culturally Responsive?

“Assessment practices do far more than provide information; they shape people’s understanding about what is important to learn, what learning is, and who learners are.” (Moss, 2008, p. 254)

Over the last few years, I started to hear the words “culturally responsive assessment” in conversations with educators in states such as New Mexico and Hawai’i. I wondered what makes assessment culturally responsive. In what ways and under what conditions can a classroom assessment or large-scale standardized test represent culturally responsive educational values?

I also started to hear different terms beyond culturally responsive, including culturally sensitive, culturally relevant, culturally sustaining. I wondered: What’s the difference among these terms and how should/can culture affect the ways in which we think about teaching, learning, and assessment?

Getting Clear on the Meaning of Terms

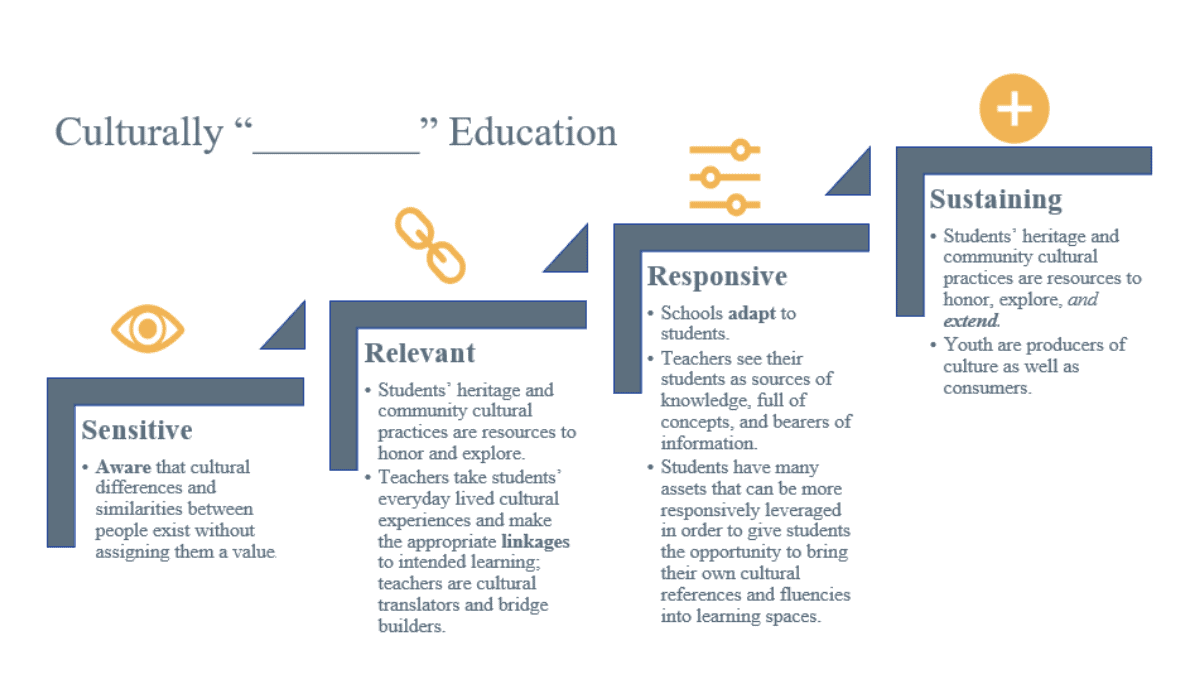

Many terms are used to describe the relationship among culture, curriculum, instruction, and assessment. As my colleague Jeri Thomspon addressed in a previous post, these terms have evolved over several decades and will likely continue to evolve. For example, I just recently heard “culturally revitalizing.” These terms: culturally sensitive, relevant, responsive, and sustaining are related yet distinct. I pulled from many sources to create the illustration below, which summarizes the various terms.

The icons included in the illustration are intended to illuminate the differences among these terms. Notice that the terms are represented in a step ladder fashion. Instruction and assessment cannot be culturally sustaining without first being culturally sensitive, relevant, and responsive.

- Culturally sensitive: The eye is meant to represent awareness—awareness that cultural differences and similarities between people exist without assigning value to them.

- Culturally relevant: The chain link represents intentional linkages between students’ heritage and community cultural practices and the learning that takes place in schools. Teachers link students’ cultural identities with their academic identities when they act as cultural bridge builders and translators between students’ everyday lived cultural experiences and the intended learning targets.

- Culturally responsive: The toggle image represents adaptation. Schools adapt to students. Students have many assets that can be leveraged, and schooling can be adapted to the students who walk through the classroom doors.

- Culturally sustaining: The addition sign represents extension where students’ heritage and community cultural practices are resources to honor, explore, and extend.

Recent conversations in the educational measurement field have raised questions about the extent to which large-scale standardized tests (e.g., state annual achievement tests, commercially available interim assessments) can be or even should be designed and implemented in ways that are more culturally sensitive, let alone culturally relevant, responsive, or sustaining.

The Challenge Issued to Large-Scale Standardized Testing

The challenge to make large-scale testing more culturally responsive has focused on

- what knowledge, understandings, and skills are privileged and therefore define the measurement constructs assessed on large-scale assessments; and

- how tests and test items can be designed with more attention to students’ cultural identities (see, for example: Randall, 2021 and Lyons, 2021).

The What: Can an assessment be culturally responsive if the standards to which it is aligned represent dominant culture values and funds of knowledge? Redefining constructs assessed requires reviewing states’ adopted content standards and paying more attention to what cultures are privileged in those identifications of what is important to learn at each grade level.

The Office of Hawaiian Education (OHE) provides a clear example of this type of standards re-definition in their Hawaiian language immersion schools (i.e., Kaiapuni schools). In a recent REL Pacific webinar, Kau’i Sang explained how OHE started by creating new standards—Hawaiian language arts standards in lieu of English language arts standards—and different science standards that reflected the cultures and communities in Hawaii. These new or revised standards are then used as the basis for the Kaiapuni Assessment of Education Outcomes (KA’EO) assessment administered in all Kaiapuni schools for school accountability purposes.

The How: Under current best practices, large-scale test items are often scrubbed of any cultural context in an effort to be ‘culturally sensitive and not biased’. Jennifer Randall argues in a recent article, however, “[w]e know students—especially marginalized students—do not experience the world including schooling in ways that are context-free, so the question becomes why do we insist that they experience assessments in this way?” (p. 1).

Dr. Randall provides a sixth-grade math example that she argues would likely be removed from a state test during a sensitivity and bias review because of the context. The context is a person, Marcellus, who is “cooking hot meals to hand out to a small group of twelve Black Lives Matter protesters demonstrating against separating families held at the U.S./Mexico border” (p. 2).

The questions Dr. Randall invites us to consider include: For whom is the assessment context/scenario controversial? Is cultural neutrality a myth and actually racist because it defaults to the dominant culture?

The Challenges Ahead for Large-Scale Standardized Assessments

The challenges we face in making large-scale standardized testing culturally responsive are directly related to what ‘standardized’ means and to the intended purpose and use large-scale tests are designed to serve. Assessments are standardized when the test design, construction, assembly, administration, and scoring procedures and protocols are intended to be the same across students so that inferences from student test scores can be directly compared.

In other words, standardization means that variations in test design, administration, and scoring are eliminated as much as possible. And more standardization is usually required when test scores are intended to be used for high-stakes purposes such as school accountability.

Of course, standardization is the opposite of individualization. And without individualization, which considers the cultural identities of the students taking the test, how can a test represent culturally responsive educational values?

While it seems possible that state or off-the-shelf commercial interim standardized tests could become more culturally sensitive over time as industry practices change, it is unclear to me the extent to which large-scale standardized tests could be designed and implemented in ways that are culturally relevant, responsive, or sustaining.

Culturally relevant assessment requires linkages between each student’s everyday lived cultural experiences and the test items or stimulus materials. Culturally responsive assessment would require tests that adapt to each student’s cultural identities. Culturally sustaining assessment would require tests that extend youth culture.

Given that what is culturally relevant, responsive, or sustaining for one is not culturally relevant, responsive, or sustaining for all, it seems there is a significant challenge ahead for large-scale standardized tests as the level of individualization needed is in direct opposition to the way these tests are designed and the intended uses of these tests within state or district accountability systems.

Is the solution then to stop worrying about standardization?

If it were possible to create domain sampling approaches or apply other methods to link or adapt a large-scale standardized test to the student, do we want there to be a Latinx test, a White test, or a Black test? Doesn’t this approach run the risk of simply reducing individuals to one identity—and likely a highly stereotyped monolithic and flattened identity— that does not fully represent a student’s heritage and community cultural practices?

Identifying the source(s) of the problem (e.g., state content standards, standardized test design, accountability systems) and solutions that address those problems are not simple. My former colleague, Charlie DePascale, recently wrote in a blog post about how a goal of ‘engaging and culturally relevant large-scale testing’ is tricky because we have traditionally wanted ‘students to be able to apply their knowledge and skills beyond contexts that are engaging and culturally relevant.’ And yet we know that continuing to operate under the current system, which places a disproportionate emphasis on large-scale standardized testing, supports dominant cultural values about what is important to learn and how that learning will be quantified (see Pamela Moss’s quote from the beginning of this post).

Conclusion: The Solution Requires Balance

Classroom systems are obviously affected by state content standards and accountability pressures, but teachers can (and do already) adapt their curriculum, instruction, and assessment practices to their students. Think of the way teaching and learning practices differ across grade spans and content areas, as two simple examples. Why couldn’t cultural and linguistic identities be woven into the fabric of classroom instructional and assessment systems by design to support all learners? Dr. Llosa’s recent keynote address at the 2021 NCME Classroom Assessment conference is a great example of cultural responsiveness by design. Other student-centered approaches to teaching and learning also exemplify the ways in which classrooms can foster and support students’ cultural and other identities.

One way to promote culturally relevant, responsive, and sustaining assessment is to refocus our attention on classroom curriculum, instruction, and assessment, while not ignoring changes around cultural sensitivity that can occur with large-scale standardized tests.

Culturally relevant, responsive, and sustaining assessment practices should occur and are completely appropriate for classroom instruction and assessment. It is for this reason that prioritizing classroom assessment systems, particularly those that support culturally responsive and sustaining mindsets, is critical.

To learn more about a Culturally Responsive Classroom Assessment Framework that could potentially support such mindset and practice shifts, see my previous blog post.