Shifts in Student Enrollment: Should They Affect Test Score Interpretations?

A look at the relationship between achievement patterns and enrollment

This is the first in a series of posts by our 2024 summer interns, based on the assessment and accountability projects they designed with their Center mentors. Mara McFadden, a doctoral student at James Madison University, worked with the Center’s associate director, Chris Domaleski.

In the wake of the COVID pandemic, declines in student achievement have been widely documented, elevating the focus on academic recovery following learning disruptions. At the same time, researchers have documented significant declines in public school enrollment, suggesting that the makeup of K-12 schools could be shifting.

I wondered how those shifts should affect the way we interpret student achievement data, so I designed a research project to shed light on this question.

In a nutshell, I found that at the state level, the relationship between enrollment declines and student achievement is modest. However, the findings are more complex if one examines enrollment at the district and school levels.

In this blog post, I’ll share highlights of my findings. The big takeaways:

- States have experienced greater declines in K-12 public school enrollment than in their school-aged populations.

- There is a weak negative correlation between the changes in performance on state tests and the changes in enrollment.

- Generally, as school enrollment declined, average test scores increased, and vice-versa.

- While overall effects were modest, that changes when enrollment declines are sizeable. Schools with more pronounced declines in enrollment experienced moderate increases in scores, and schools with pronounced increases in enrollment experienced moderate declines in scores, on average.

- The pattern became more complex as I looked closer: schools with lower overall test scores that experienced the greatest enrollment declines experienced larger increases in scores compared to similar schools with the greatest enrollment increases

I divided the study into two phases to explore (1) the nature and magnitude of enrollment shifts before and after the pandemic and (2) the impact of enrollment shifts on interpretations of longitudinal academic performance.

Exploring Enrollment Shifts Before and After COVID

In phase one, I collected data from the Common Core of Data (CCD) (National Center on Education Statistics, 2024) and the U.S. Census Bureau (2024). I gathered total enrollment for each of the 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C. for the academic years 2017-18 to 2022-23 and disaggregated them by grade level (kindergarten, 5th grade, 8th grade, 10th grade), gender, and race/ethnicity. I calculated percent change of enrollment for all states from 2020-21 to 2022-23. I chose these years to minimize the confounding effects of pandemic disruptions. I collected longitudinal school-aged population data as a comparison for enrollment shifts.

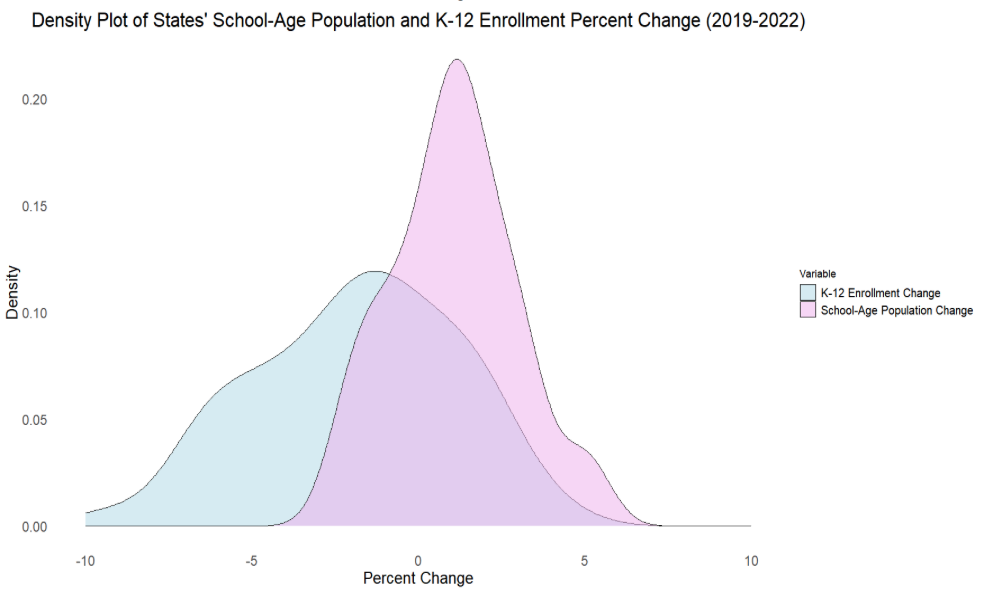

Figure 1 illustrates two overlaid distributions: the percentage change in public school enrollment and in school-aged population across the states from 2019 to 2022. It shows that generally, states experienced greater declines in enrollment than in their school-aged populations.

This is notable because some have theorized that well-documented declines in birth rates could be driving declines in public school enrollment. These data appear to cast doubt on that theory, but we’d need more research to better explain that relationship.

Figure 1.

For phase two, I collected state test results at the school level for two large states that experienced declines in enrollment that were among the largest nationally between 2021 and 2023. I gathered mean scale scores (MSS) in math and English/language arts (ELA), test-participation data and enrollment data for 5th and 8th grades for each sampled state. I chose these four academic years so I could examine the impacts of enrollment shifts on performance trends in the three years before (2016-17 to 2018-19) and after (2020-21 to 2022-23) the pandemic. I selected 5th and 8th grade as phase one results revealed that these were the two tested grade levels with the steepest declines in enrollment from 2019-2023.

Findings: The Relationship of Enrollment and Test-Score Declines

Results from school analyses in both states indicate that there is a weak negative correlation between changes in MSS and enrollment. Using State A as an example, the correlation between the percentage change in 5th grade enrollment and change in ELA MSS was:

- -0.137 for the academic years 2020-21 to 2022-23

- -0.105 for the academic years 2016-17 to 2018-19

I’m highlighting only the results in 5th grade ELA in one of the states I studied, but these results reflect the patterns I found in math, and in eighth grade, for both states.

In both periods I studied—the three years before the pandemic and the three years afterward—schools with more pronounced declines in enrollment experienced moderate increases in ELA MSS, and schools with more pronounced increases in enrollment experienced moderate declines in ELA MSS on average.

For example, from 2021 to 2023, schools in State A with 5th grade enrollment declines larger than -30% experienced an average increase in 5th grade ELA MSS of .19 standard deviations (see Table 1). Schools in State A with enrollment changes smaller than 30% experienced an average decline in ELA MSS of .21 standard deviations (see Table 1). I observed similar patterns between 2017 and 2019 but observed fewer schools in these pronounced-decline categories.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of State A schools’ change in 5th grade ELA MSS from 2021-2023 by categorized enrollment change

| % Enrollment Change | # Schools | Standardized Mean Change | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| < – 30% | 53 | 0.191 | 0.83 |

| -30% – -20% | 96 | 0.133 | 0.664 |

| -19% – -10% | 189 | 0.031 | 0.671 |

| -9% – 0% | 252 | 0.048 | 0.656 |

| 0% – 9% | 251 | -0.054 | 0.671 |

| 10% – 19% | 156 | -0.109 | 0.712 |

| 20% – 30% | 76 | 0.070 | 0.712 |

| > 30% | 74 | -0.210 | 0.784 |

Additional investigation revealed that schools with lower initial performance experienced an average increase in MSS, regardless of enrollment shifts. The increase in MSS becomes less pronounced, however, as the percentage change in enrollment increases.

Specifically, lower-performing schools that experienced declines in enrollment of at least 30% from 2021-2023 experienced the highest average increase in MSS (.45), whereas lower-performing schools that experienced 30% or larger increases in enrollment experienced the lowest average increase in MSS (.22). This suggests there is something more than ‘regression to the mean’ occurring.

A similar pattern emerged in schools with high initial enrollment. The findings reported on 5th grade ELA data from State A were similar to those at other grade levels (5th and 8th grades) and in both subject areas (ELA and Math) for both states.

What Now? Limitations and Considerations

The findings from this initial exploration of the relationships among enrollment shifts and performance trends are meant to provide insight and suggest where further investigation may be appropriate. My research cannot establish causality; it can only describe the relationships among the factors I explored.

One key insight from my study is the notable variability, from school to school, in the effect of enrollment shifts on achievement.

This variability represents an important limitation, preventing larger-scale generalizations about the effects of enrollment shifts on achievement, but it also provides important context for the main recommendation I’d make based on my findings:

Schools that experience pronounced enrollment shifts should consider the impact of those trends when interpreting achievement patterns over time.

Since many factors shape student achievement, shifts in enrollment aren’t the only explanation for trends in test results. Access to high-quality curriculum and instruction, district and state policies and interventions, and many other factors undoubtedly also contribute to student achievement results. Schools and districts would need to investigate their unique contexts to determine which factors shape their student achievement results.

Case studies in which district and school personnel in cities that experience pronounced enrollment shifts speak about their perspectives on performance trends have the potential to uncover more. Moreover, the use of statistical adjustments in student-level analysis may better disentangle the impact of enrollment on student achievement (e.g., propensity score matching).

These findings certainly raise many questions that merit further study regarding the influences on enrollment and the association with achievement. I hope this research helps inspire those studies, since the stakes—student learning post-pandemic—are so high.