Fall Educational Assessment Information: What You Need and How to Get It

How Selecting the Appropriate Assessment Can Help Inform Instruction This Fall

Schools have dismissed students to enforce social distancing and have implemented remote learning for the rest of the 2019-20 school year. Learning has probably been more uneven than usual across students, classrooms, grades, schools, districts, and even states, which presents challenges for instructional planning, including planning for fall educational assessment. Selecting an appropriate assessment to inform instruction requires understanding what assessment information you need, and what information the assessment provides

I focus on instructional planning because I am skeptical about substituting fall testing results for spring results in school accountability systems. Among the daunting challenges to accountability use are:

- estimating precisely how much fall results should differ from the previous spring results, and

- if used for growth, counteracting the fact that fall-to-spring growth scores can be intentionally manipulated by having lower scores in the fall.

When students report back to school in the fall (hopefully!), what assessment information would you like to have to support good instruction and curriculum planning? Although I focus on instruction below, most major instructional changes require concomitant curricular changes. For example, if a teacher plans to teach more of something, that teacher almost always has to decide to teach less of something else.

A central takeaway of this post is that different uses require different kinds of assessment information, which requires different kinds of assessments. I’ve discussed this fundamental point and illustrated it regarding differences between a summative end-of-the-year assessment and an end-of-the-first-instructional-unit interim assessment (see here), as well as for using interim assessments to substitute summative assessments (see here).

I also emphasized this point for different interim assessments that might be used to inform remedial versus “new” instructional efforts (see here), and for interim assessments designed to inform instruction about student strengths/weaknesses during the year (see here and here).

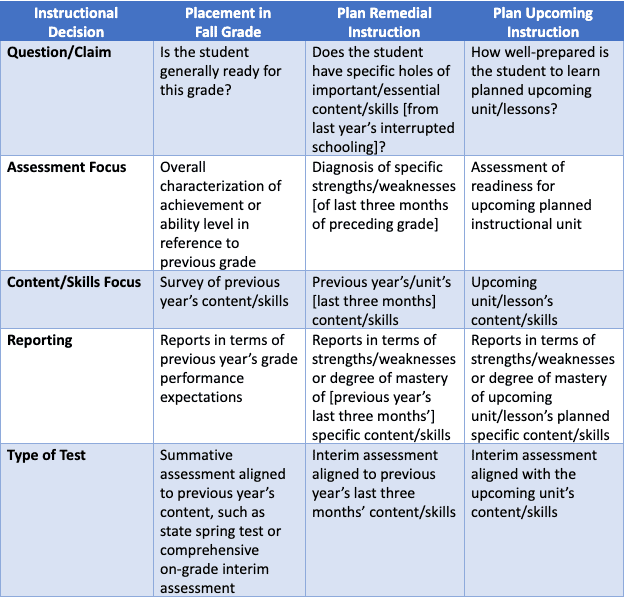

I’ll apply these principles in discussing three likely scenarios for those considering assessing students in the fall:

- General placement in a grade or “track”;

- Remedial instruction to address weaknesses in student knowledge/skills, especially after three months of disrupted schooling due to the coronavirus;

- Getting an idea of what students know in order to prepare and differentiate instruction for the new school year/units.

I’ll illustrate why each of these uses requires assessing different content/skills and thus implies a different assessment.

After discussing these three uses, I’ll briefly review two other important questions:

- How could you tell how well-suited an assessment is for your particular purpose?

- How can you tell whether your instructional plans are cost-effective?

Different Assessments for Different Purposes: Three Fall Instructional Uses

The assessment information you need depends on what you are going to do with it. To say that you want to “inform instruction” is not specific enough. Two main considerations when thinking about assessment information to inform instruction are:

- What is the scope of the content/skills needed for a particular decision?

- Is the decision as broad as placing a student in a grade, or perhaps as focused as placing a student in a remedial group based on weaknesses in specific content or skills? The general placement in a grade will focus on a survey of all the previous year’s content/skills, while the more focused remedial assessment will focus on a subset of the previous year’s content/skills, such as those that should have been covered in the last three months when instruction was disrupted.

- What is the relation to past, current, and future planned instruction?

- Will the decision inform something that has already been instructed, or inform instruction on content that has yet to be instructed? To distinguish between these two uses, I use the terms “remedial assessment” and “pre-assessment.” A key distinguishing characteristic for fall testing is that remedial assessment will be looking back to content that should have been taught in the previous grade, while pre-assessment will be looking forward to content to be introduced in the current grade.

The previous-year summative and next-unit pre-assessment are likely unchanged by the events of 2020. If you want an assessment to inform possible remedial instruction focused on the interrupted schooling of 2020, then that will probably require a customized interim assessment, unless the interrupted curriculum happens to line up with a pre-existing last quarter or last unit assessment.

How Can You Tell How Appropriate an Assessment is to Your Purposes?

This simple example illustrates how different instructional uses usually require different types of information, and therefore different types of assessment. In particular, it would be impossible for an assessment to include a general survey of the previous year’s content/skills, but also be focused on the content/skills of the last three months of the previous year’s curriculum, while still including content from the beginning of the current year.

So, if you are thinking of administering a test next fall for an instructional purpose—one of those discussed here, or any other—what should you look for in an assessment? At least:

- Is the test intended to be used for your purpose? You should not rely on what marketing materials say about intended uses. This point is critical, but unfortunately, in our experience, assessments often claim to be appropriate for purposes for which they are not actually designed. Hint: If an assessment claims it is good for multiple, quite different purposes, read the fine print in the test documentation very carefully.

- Does the documentation show that the assessment is based on the relevant content/skills; e.g., if you are interested in diagnosing strengths/weaknesses of the last three months of last year’s curriculum, are those content/skills specifically included in the assessment, and are other, less relevant content/skills not included?

- Do the test reports provide the information you need for placement, remedial instruction, or pre-assessment? In an upcoming post, I will discuss the critical importance of content-related feedback for informing instruction, and the strengths and limitations of the two most common ways tests are designed to provide content-specific information.

Note that a claim of being aligned to the state content standards is not sufficient. An assessment administered for any of the purposes discussed here should be aligned to the state content standards and your curriculum.

If there is no publicly-available documentation you can use to determine how well your needs are matched by the specific content addressed in the assessment, then there is a major hole in the validity evidence and it will be more difficult to conclude that the assessment is appropriate for your purposes.

In this post, I have discussed the relatively simple case of evaluating the use of an assessment – likely an existing assessment – for a particular purpose. The larger process of deciding whether to implement a new assessment program or to select a new assessment requires a more systematic and complete evaluation of how well an assessment matches your intended uses and would require answering a broad series of questions:

- What do you want to do?

- What are your primary ways to accomplish what you want to do?

- What information do you need?

- How could assessments help provide that information?

- How do you know which specific assessments can provide that information?

- Are the assessments of sufficient quality that you can trust and use them?

- How well could/have you used the information to achieve your goals?

The Interim Assessment Toolkit, whose development at the Center for Assessment is being led by my colleagues Erika Landl and Juan d’Brot, leads a user through a thorough process. It can be found here.

How Can You Tell Whether Your Instructional Plans Are Appropriate and Cost-Effective?

In this post I have emphasized the importance of specifying in detail what information you need so you can tell whether an assessment is designed to provide that information. But perhaps more important questions are, “how do you know that what you are planning to do will actually make a difference?” And, “is it the best use of time and other resources; i.e., is it cost-effective?”

For example, we started with an assumed use of identifying students who had weaknesses in some specific areas of content knowledge and skills that were taught last year and are necessary to succeed in the current year. But a valid assessment of where the child is does not automatically guarantee that your instructional support will be effective.

The assumption is that you (the school, the child’s teacher, the child themself) will do something instructionally that will help the child acquire the needed content knowledge and skills. That assumption means you have a) an instructional plan tailored for your specific students; b) your plans can be carried out and will lead to the longer-term goals you want, and c) you are continuously monitoring and improving your plans.

Implementing Your Plan & Resolving the Real-World Scenarios You’ll Face

In closing, I leave you with three sets of questions that should be asked when planning, implementing, and evaluating the effectiveness of any instructional intervention.

How confident are you that your planned instruction is appropriate for your students?

- Do you know what the child knows well enough to learn the next curricular content with typical supports, and what the child has weaknesses with that will need more extensive supports—and how those are similar to and different from the other children in the class?

- Why are you confident that your planned instruction will help the child learn what they didn’t learn last year? Do you know how instruction was presented last year when the child didn’t learn the content/skills sufficiently? Does your planned instruction focus on helping with conceptual understanding, more practice, different scaffolding, targeted feedback, socio-emotional encouragement, etc.?

How do you know that your instruction will be effective in helping your students learn and catch up?

- How confident are you that the teachers, students, and others can implement the instructional plan with the needed fidelity? For example, does the teacher have enough instructional repertoire to incorporate the differentiated assessment information? Does the teacher have enough organizational bandwidth to carry out the differentiated instruction plan, given the needs of their student load of around 25 (elementary) or 125 (middle or high school) students?

- How confident are you that if the child does what is expected and laid out, they will catch up to their peers, grade-level curriculum, and be on track to becoming college/career ready? Too many remedial curricula are of dubious effectiveness and are designed never to have the student catch up.

How do you know you are making needed adjustments so you can “know early, act promptly”?

- How confident are you that you and others will know how well your/their plans are working and are making needed adjustments?

- Are there regular program evaluations and policy reviews (for example, see here) to identify and address any systemic barriers to improved learning?