To Adapt or Not to Adapt? That Is the Question

Deciding between fixed-form and adaptive tests? Get clear on purpose.

When it comes to state assessments, one question continues to surface: should we use adaptive or fixed-form tests? It sounds like a technical decision, but it’s really a philosophical one. The answer depends not on what technology can do, but on what the system is designed to achieve.

Recently, I found myself in a virtual meeting with state officials. There, as in many meetings with decision-makers, the discussion treated adaptivity as a marker of innovation, as if the move to a computer-adaptive model automatically signals progress.

But adaptive testing isn’t inherently better; it’s simply designed to solve a different set of problems. The real work lies in clarifying what problem we’re trying to solve in the first place.

Framing the Question

Every assessment design begins with a question: What are we trying to measure (and how)? In more technical terms, that means clarifying the claims we want to make about what students know and can do. We need to answer that question before we ask if we are chasing more efficient measurement, or a more transparent design, or better alignment with recently refined standards. Overall, there may even be a desire to understand if we are getting a stronger return on investment over time. (Full disclosure: I’m not a fan of ROI in educational settings because of the complexity of inputs and outputs and the lack of clear lines between the two.)

Fixed-form assessments give every student a predetermined set of items, whereas adaptive assessments give students different items by adjusting difficulty based on whether they answer correctly or incorrectly.

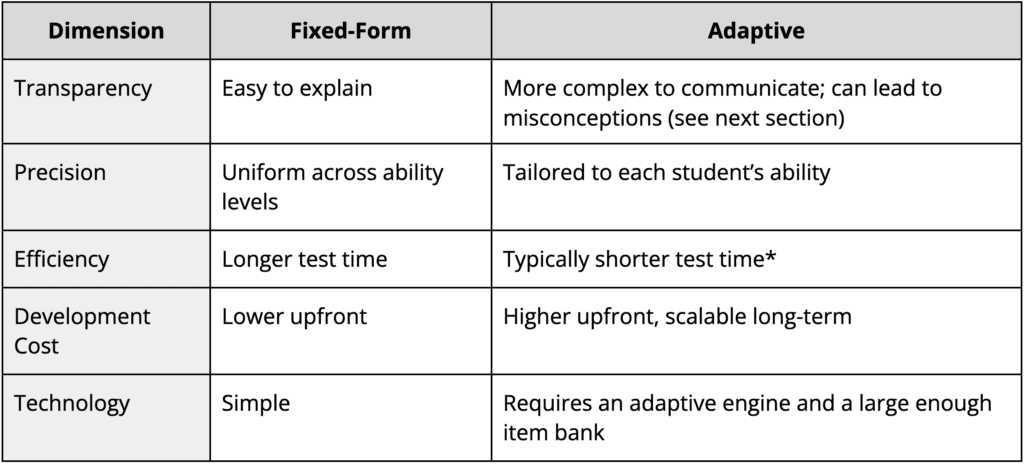

Both fixed-form and adaptive tests can support these goals, but each one elevates different values. Adaptive tests tend to emphasize precision and efficiency. Fixed-form tests prioritize simplicity and transparency. Neither is right or wrong—they just reflect different goals.

To reach those goals, design conversations will unfold. And each conversation should be anchored by a guiding principle: design decisions should serve the assessment’s purpose, not its technology.

Two Paths to the Same Goal

At their core, fixed-form and adaptive assessments are simply two paths to the same destination: accurate, fair, and useful measurement (in their ideal state).

Fixed-form assessments give every student the same set of questions or a similar set of questions (known as a parallel form). They’re straightforward to explain to the general public, educators, and students, and are easy to equate across administrations. Because everyone takes the same test or set of tests, they often feel more “fair” to the public. Also, if the fixed form is not secure, it can be released to the public, educators, and students.

Adaptive assessments, on the other hand, adjust the difficulty of items (or sets of items) based on each student’s responses. This can yield more precise measurement for individual students (especially at the upper or lower ends of the performance distribution). It can also reduce testing time (though much of that efficiency is lost in state-summative settings because of the requirement to cover the breadth of the standards taught over the course of one or multiple years).

Adaptive tests often feel more personalized, though they can be harder to explain to educators and the public and require more sophisticated technology and a larger investment in item development.

Both designs produce comparable results when built and scaled appropriately. The question is not whether one is better, but which better fits a system’s goals, capacity, and communication priorities.

Navigating the Tradeoff Space

Every design choice involves tradeoffs. In adaptive testing, the benefits of efficiency and precision come with greater technical complexity and higher upfront costs. Fixed-form testing trades those efficiencies for predictability and simplicity.

*Adaptive testing efficiency is always constrained by blueprint requirements and content coverage.

Each dimension carries tradeoffs that may be valued differently based on point of view. Policymakers tend to value transparency. Technicians value precision. Teachers and students often appreciate shorter, more focused tests (if you can get them). The art lies in balancing these perspectives within the boundaries of the assessment’s purpose and design goals.

Alignment and Misconceptions

Adaptive testing can sometimes be misunderstood. Because students see different sets of items, some worry that the results aren’t comparable. In reality, comparability comes from the scale, not from everyone taking identical tests. Through statistical calibration and equating, both models can yield scores that sit on the same measurement scale.

Others worry that adaptive tests may “lock” students into an unfair path—that an early mistake limits their opportunity to show what they know. But adaptive systems adjust difficulty, not content. The goal is to match items to a student’s current ability estimate, not to reduce exposure to the standards being measured.

In fact, adaptive designs can continue to align fully with revised or streamlined standards as long as the test blueprint reflects those changes. The technology should respond to the blueprint—not the other way around.

Design Lies Downstream of Purpose

No matter how sophisticated the technology, the foundation of good assessment design is clarity of purpose—and the goals that flow from it. Adaptive and fixed-form models both can produce valid, reliable and fair results. The right choice depends on what the system values most.

If a state’s vision emphasizes efficiency and precision, an adaptive design might be the right fit, especially for large-scale testing programs where seat time and measurement precision matter. If the vision emphasizes simplicity, transparency, and communication, a fixed-form model might better serve those goals.

Ultimately, design should flow from the system’s theory of action: what the assessment is meant to inform, for whom, and how? When the design aligns with that purpose, the system earns credibility and coherence.

To adapt or not to adapt isn’t really the question. The real question is: does our assessment system serve its purpose—or does it serve its technology? Assessments should serve the broader goals of the system to support learning, not the other way around.