A Deep Dive into Formative Assessment in a Remote or Hybrid Learning Environment (Part 1)

What’s the Same and What’s Different about Classroom Assessment in 2020-2021?

As school restarts this fall, many teachers and students are facing different learning environments than the typical back-to-school realities – including when it comes to formative classroom assessment.

COVID has reshaped teaching and learning in ways that could make a teacher or other educational leader wonder—what’s the same and what’s different about classroom assessment in a remote or hybrid learning environment?

To answer that question,we build off of Scott Marion’s recent post discussing how the Classroom Assessment Principles to Support Teaching and Learning (Shepard, Diaz-Bilello, Penuel, and Marion, 2020) can serve as a framework for assessment during remote instruction. We describe a continuum of dimensions that affect the degree of instructional and assessment shifts in a remote or hybrid learning environment, and provide examples to show how the continuum applies to formative assessment processes. Our next post will focus on remote applications of summative classroom assessment.

Defining Formative Assessment

We adhere to the definition of formative assessment put forward by the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO, 2018, p. 2), as “a planned, ongoing process used by all students and teachers during learning and teaching to elicit and use evidence of student learning to improve student understanding of intended disciplinary learning outcomes and support students to become self-directed learners.” Not only can we use this definition in the context of remote student learning, but it can be expanded to include any aspect of student experience that affects their learning and development.

The principles of formative assessment are the same in a remote, hybrid, or in-person learning environment. For example, strategies that support the implementation of effective formative assessment still include: (a) clarifying, understanding, and sharing learning intentions; (b) engineering effective classroom discussions, tasks, and activities that elicit evidence of learning; (c) providing feedback that moves learners forward; (d) activating students as learning resources for one another; and (e) activating students as owners of their own learning (Wiliam, 2011).

However, enacting formative assessment will differ in remote compared to in-person contexts. For example, what teachers ask students to do, how teachers interact with students, and/or how teachers collect evidence from and give feedback to students may all differ in remote compared to in-person instruction.

Classroom assessment is integrally related to curriculum and instruction, so changes in curriculum and/or instruction should lead to shifts in classroom assessment—especially formative assessment because of its inseparability from instruction. Formative assessment practices are different in a remote or hybrid learning environment than in an in-person learning environment because teaching and learning activities are different.

A Continuum for Describing How Formative Assessment Might Shift in a Remote Setting

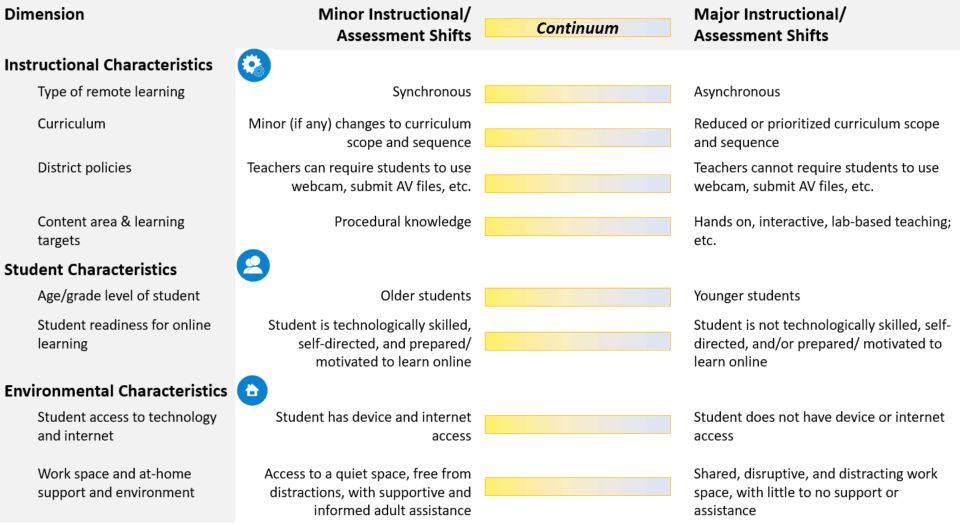

There are at least three major dimensions—instructional, student, and environmental characteristics—that shape the ways in which formative assessment is planned and implemented in remote or hybrid contexts. These dimensions have implications regarding the degree of instructional and assessment shifts likely required of teachers.

We organized these dimensions along a continuum of the degree of instructional and assessment shifts likely required to operate in a remote context (see Figure 1). For example, factors such as type of remote learning (synchronous or asynchronous), curricular prioritization, policies around student webcam use, and type of learning targets, all fall within the instructional characteristics dimension and must be evaluated when designing formative assessment approaches.

Similarly, there are student characteristics such as the age/grade level of students and student readiness for online learning that also affect the practical shifts required in the classroom assessment space. The last category, environmental characteristics, relates to student access to technology and the internet, as well as at-home work space and supports. There could be other environmental realities that affect classroom instruction and assessment in a remote or hybrid context. These environmental realities include students’ experiences during remote or hybrid learning and how those have affected their ability to attend to learning, motivate themselves to do their best under difficult circumstances, and so on.

The dimensions are not independent, but operate in an overlapping and interconnected fashion such that a profile of remote learning environments is constructed.

In the next section, we provide examples of practical differences in formative assessment when considering different profiles.

Figure 1.

Continuum of Instructional and Assessment Shifts in a Remote Learning Environment

Practical Differences in Formative Assessment Practices in a Remote Setting

Consider a classroom profile where asynchronous instruction is taking place with older students, most of whom are technologically skilled and have access to devices and the internet. Compared to typical in-person instruction, the teacher is constrained as to when and how they can collect formative assessment evidence because the teacher cannot monitor or adjust instruction in real-time. Instead, in order to figure out what students have learned, what misconceptions they may still have, and what questions remain unanswered, the teacher will need to use an online tool to collect that information from students and return appropriate feedback after students have watched the pre-recorded instruction.

Now consider a different profile where there is synchronous remote instruction with early elementary students who are not technologically skilled but have access to devices and the internet. The teacher can use before-, during-, and after-instruction formative feedback cycles to monitor and adjust real-time instruction as in an in-person setting. However, the remote setting requires the teacher to change what they ask students to do, how they interact with students, and how they collect assessment evidence. The teacher may use the webcam feature on students’ devices so they can observe students working at home. The teacher may also meet with smaller groups of students to ask probing questions and listen to student thinking—without requiring students to provide that formative information through an online tool not easily accessed by K-2 students.

Conclusion

Our hope in clarifying the distinctions between what is the same and what is different in formative assessment practices in in-person and remote/hybrid learning environments is to help educational leaders and teachers know what, whether, and how to shift instructional and assessment practices to improve student learning.

Though the tools, applications, processes, and procedures used to collect evidence of student knowledge and skills, the nature of interactions between teacher and student, and what students are asked to do may differ in a remote or hybrid learning environment, the foundations of high-quality formative assessment remain vital. Energy and focus should be placed in supporting practical solutions to address different classroom profiles with the goal of trying to support the essentials of formative assessment as much as possible.