Part 2: Measure Twice, Cut Once When Developing Large-Scale Assessments

Planning for An Appropriate Test Development Timeline

In part one of this series, I addressed the risks associated with cutting corners in the test development process for large-scale assessments and described the characteristics of stronger approaches. In this post, I discuss the test development timeline (and test deployment timeline) more specifically.

How Long is the Test Development Timeline?

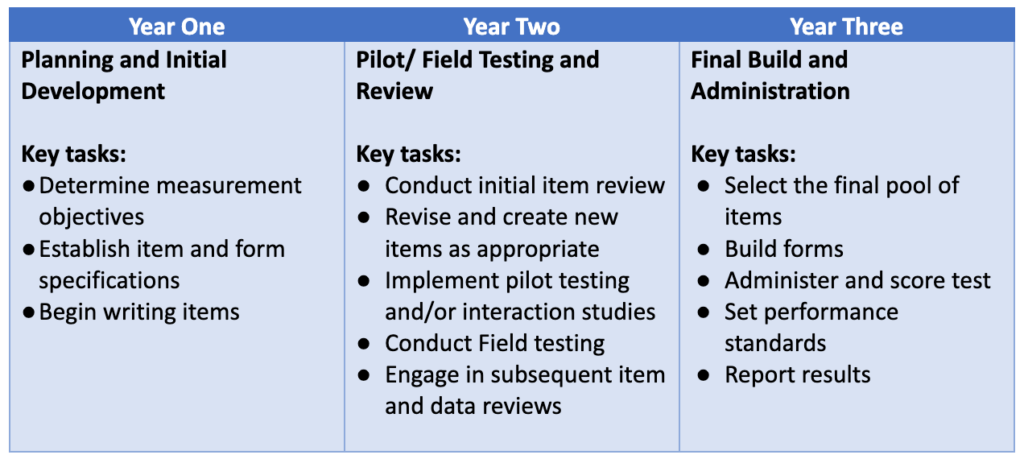

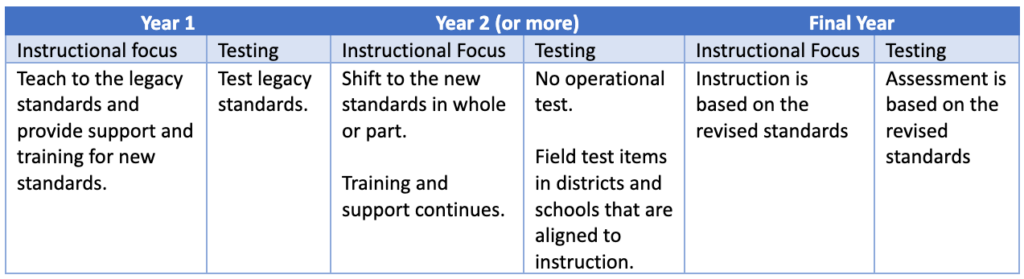

How long does it take to develop a large-scale test from start to finish? The timeline depends on a number of factors but three years at a minimum is a good rule of thumb. The following table shows what a three-year cycle could look like.

There are a number of activities that are not addressed in this illustrative timeline. For example, state education agencies may need multiple years to work with stakeholders and policy leaders to determine priorities for a new assessment system and to complete the procurement process to select qualified contractors. These activities all occur before the key tasks described in year one.

Also, each of the phases listed above might take longer based on the specific complexities within a state. For example, some programs may require more time for development, pilot, and field testing, especially if the scope is broader, the objectives are more novel, and/or the proposed methods are not grounded in an established research base.

Don’t Overlook Curriculum and Instruction

It’s important to remember that achievement tests should be coherent with curriculum and instruction. Therefore, the test development process must be compatible with corresponding activities to ensure that teachers have the time, resources, and support to provide students the opportunity to learn prior to the first operational test administration.

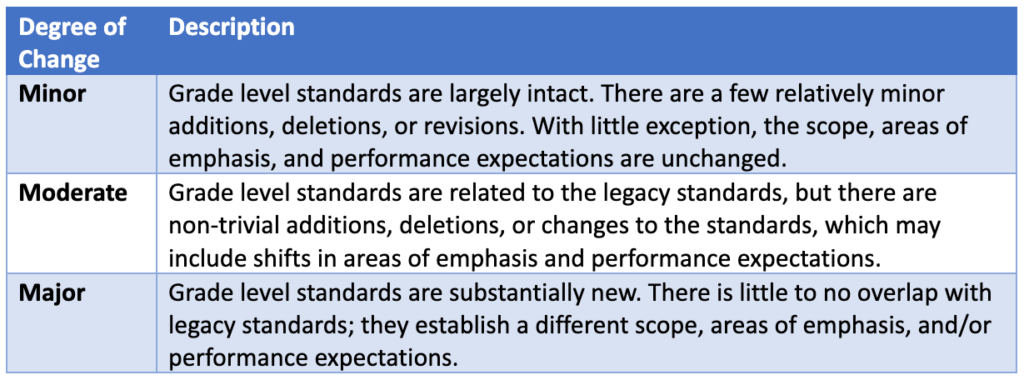

When a state adopts new or revised grade-level content standards, one of the first steps it must take is to determine the extent to which these revisions require a shift in what is currently taught and tested. Very broadly, these shifts may fall into one of the following categories:

Implementing a Transitional Test if Changes to the Standards are Minor

If the changes are minor, reflecting primarily light revisions, it may be possible for the state to administer a transitional test during the test development process. A transitional test covers the overlap between the legacy standards and revised standards and includes some targeted new content to reflect the revisions for sites that are early implementers. The objective is to keep the testing program online without disturbing the integrity of the legacy test, during the time that the tests are being revised and content is being field tested. In such cases, a transition process may be as follows:

This process assumes an embedded field test model (EFT) in which field test items are added to the test as ‘try-outs’ but not scored. It’s never a good idea to administer field test items on a high-stakes test that are not aligned with the standards, even if they aren’t scored. Not only will doing so produce field test results that aren’t trustworthy, but it could disturb the operational test. For this reason, the ‘transition’ model above assumes that all items are aligned to instruction in each year.

For example, Year 2 might involve administering field test items aligned to the new standards only in districts that are implementing these standards ahead of schedule.

It’s also important that the field test sample in every instance is representative of all learners in the state.

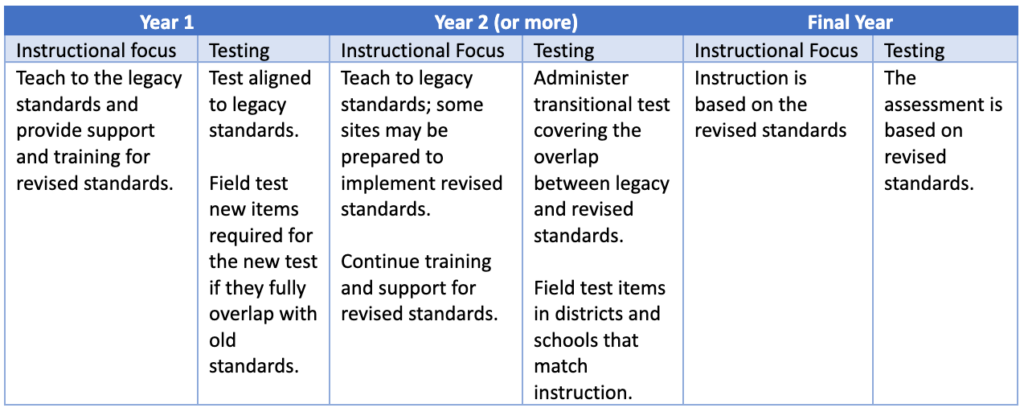

Suspending the State Test While Implementing Moderate to Major Changes to Standards

if there are moderate to major shifts in the content standards, the operational test will need to be suspended to avoid a mismatch between what is taught and what is tested. This timeline is illustrated in the following table.

The key difference in this timeline is that the operational test is offline the first time districts and schools deploy the new standards. During this time, field testing can occur as a stand-alone event (not EFT). The results are used to help build future test forms but not for any student or school stakes.

In some cases, a three-year process may not be adequate. Additional time for training, support, and targeted implementation may extend the time required. For example, a state may have multiple years of field testing content that overlap with the new standards before taking the legacy test offline to field test the new content.

In general, more sweeping changes to content standards require a longer runway to both build the new test and support desired shifts in teaching and learning.

Avoid Latent Error in Test Development

An unreasonably accelerated development process leads to what is termed “latent error.” Latent error is not unique to the field of large-scale testing. It occurs any time a poorly-designed system or unreasonable expectations inflate the likelihood of human error. For example, if a physician is asked to see too many patients in a short amount of time, the likelihood that some patients will receive inadequate care is increased.

Given the prominent role that large-scale testing plays in supporting consequential decision-making, it’s imperative to take the time and devote the resources to develop an assessment properly from the start.

The concepts and examples offered in this post are intended to be illustrative. It’s always best for states to work with their technical advisory committee (TAC) to discuss the development and deployment plan that is best suited to address their specific context and priorities.

Above all, I urge measurement professionals from all sectors to push back on unreasonable demands to accelerate large-scale development. Speeding up the process will involve either skipping steps or requiring the developer to do them faster. Either way, this eliminates or reduces the time devoted to key tasks such as planning, quality assurance testing, and review.