Zero Tolerance for Zeroes

It’s Time to Stop Pretending We Have a “100-Point” Grading Scale

Grading and grading scales are one of the most ubiquitous aspects of schooling, but it is also one of the most controversial and misunderstood. Why would I say misunderstood? Everyone knows the difference between an A and B, or between 89% and 91%, right? Unfortunately, many people think they do, but they might be surprised to learn their long-standing intuitions and beliefs do not hold up. The recent point-counterpoint playing out in Fordham Institute posts on the use of “zero grades” are a prime example of both the controversies and misunderstandings.

Carla Evans’s terrific blog series and my recent rant summarized many of the misconceptions about grades and grading scales. In case these hurdles weren’t high enough, Daniel Buck’s piece in Fordham’s newsletter about “no zeros grading policies” being the “worst of all worlds” only added to these misconceptions. Thankfully, Doug Reeves provided a thoughtful response, but I want to emphasize a few additional points.

A Personal and Professional Investment in Grading and Grading Scales

As a measurement professional, dad, and school board member for many years, grading holds personal and professional frustrations for me. Buck’s recent commentary dredged up those old frustrations.

Derek Briggs’ terrific new (2022) book, Historical and Conceptual Foundations of Measurement in the Human Sciences: Credos and Controversies, summarizes the challenges of “measuring” human characteristics such as student learning. One does not have to get far into Derek’s book or almost any other basic text about educational testing to recognize that grading is quite far from the measurement of student performance or learning that most people believe it to be.

A Little Background on Grading

Grading is theoretically conceived as a way to provide students and parents with documentation regarding a student’s performance related to the things the student is supposed to be learning in school. Unfortunately, it has become so much more than that. It is often used as a way to control student behavior and as a ranking mechanism used to sort students into different course-taking opportunities and postsecondary options (see Willis’ famous Learning to Labor, 1977). As such, grading practices have been rightfully scrutinized for perpetuating race and class inequities (Feldman, 2019).

Further, Lorrie Shepard and others have been concerned for years about how most grading practices run counter to modern theories of learning and motivation. As Caroline Wylie noted in her recent CenterLine post, “[e]ducators need opportunities to recognize the inherent unfairness of grading every piece of work while learning is still developing.”

The ubiquity of learning management systems (LMS) has only made this problem worse. Perhaps because of a noble desire to keep parents aware of how students are performing and progressing on course content, or because of educational leaders’ lack of assessment and learning literacy, teachers are pressured to enter essentially every assignment into their LMS.

Unfortunately, the problem is compounded because these management systems are often set by default to convert scores into percentages, performance levels, letter grades, etc., all of which simplify and summarize what might have been a rich depiction of student work.

Grading is Getting Personal

I said this was personal for me, so let me explain. As a teen, my very smart and now very successful son Noah was strong-willed (yes, many have mentioned apples and trees), and thought homework was an unjustified infringement on his free time. I had a hard time saying he was always wrong about this after seeing many of his assignments; however, I spent a lot of time arguing with Noah, imploring him to just play along because these grades would matter for his future opportunities. That approach worked for a bit, but even when he did his homework, it would often remain in the bottom of his backpack, resulting in him receiving a grade of zero (0) for the assignment. I was fine with Noah receiving appropriate penalties but giving kids zeroes for not turning in their homework seemed both unfair and innumerate.

I remember being at a small gathering of parents with the high school principal when I raised the grading scale issue. I tried as patiently and instructively as I could to explain to the principal that they did not have a 100-point scale, but a 40- or 50-point one at best. The principal responded, “but our teachers feel that this is an important way to teach students to be responsible.” A parent next to me jumped in to say, “he’s not making a moral argument, he’s making a simple statistical point.”

So what is this simple point?

Grading Scales and the Number Line

Andrew Ho recently summarized many of the problems with interpreting test scores, and grades by extension,

When it comes to test scores, I often say that we are “weak to numbers” (Ho, 2014). We ascribe numbers with unwarranted importance that manifests as three fallacies, that scores are 1) more meaningful, 2) more precise, and 3) more permanent than they actually are.

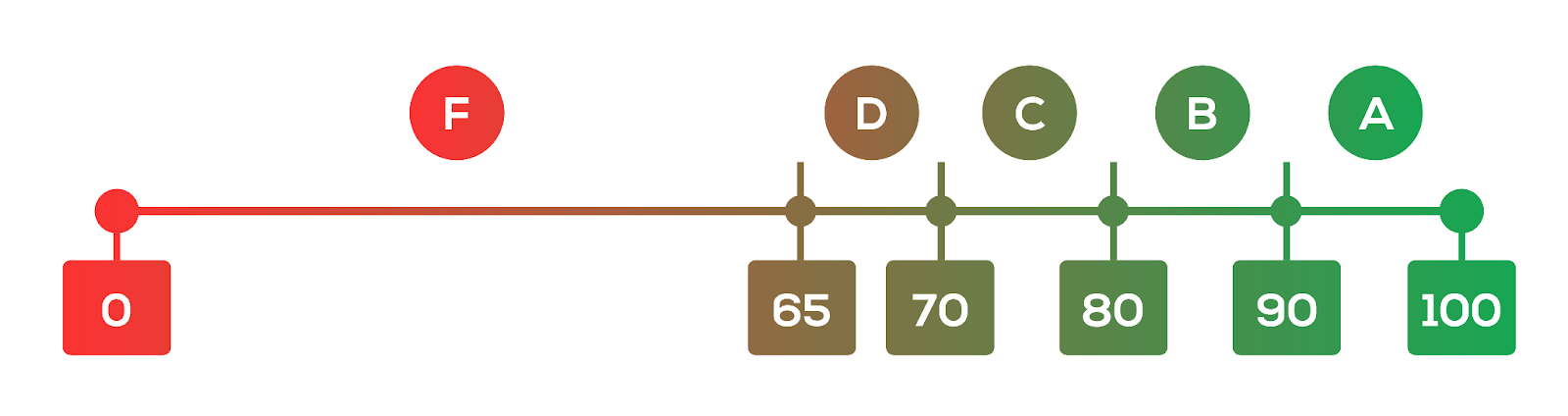

Thinking of this as a number line, a grade of A usually ranges from 90-100, a B from 80-89, and so on until we get to an F, which often ranges from 0 to 65%. How does allocating nearly two-thirds of the number line for a grade of F make any sense?

A simple thought experiment might help explain my complaint with the “100-point scale.” Assuming assignments are equally weighted, the average of scores of 0 and 100 would be 50. But if we convert these numbers to grades using the scale above and I asked you to compute the average of an A and F, most everyone would say a C. Clearly a 50 is not a C.

A student subjected to the 100-point scale would have to score 100% on two additional assignments to reach a C average (75% in this case). When we switch between two metrics (i.e., percentages and grades) intended to mean similar things and get wildly different results, something is off with one or both metrics.

Bad Math

Daniel Buck and my son’s high school principal might not worry about the results of this thought experiment because they see grades as a way to control student behavior. Besides the decades of research showing that such practices backfire and actually harm student motivation and learning, giving zero grades is just bad math.

I know that shifting from any traditional grading scheme gets parents’ attention, and not in a good way. But the research and best practices are clear that grades should be based on the knowledge and skills that students have had a fair opportunity to learn and demonstrate. If teachers need grades to control behavior, there are usually bigger problems at hand. Further, schools can always institute “behavior reports” if they want to report on things like responsibility and respect. See Carla Evans’ third post in her series for suggestions on moving forward with sound grading approaches.

For now, schools can do one little thing without reforming their entire grading approach. They can rip the number line in half and have it run from 50 to 100. This simple adjustment would result in a numeric grading scale that better matches the underlying letter grade scale and they would get to model some good quantitative reasoning and fairness for their students at the same time.

To paraphrase Ronald Reagan, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear up that grading scale!”