Diagnostic Measurement for K-12 Education

Answers to Frequently Asked Questions I’ve Received on Diagnostic Classification Models

When you hear the term “diagnosis”, I would bet that you are thinking about clinical settings in medicine, psychiatry, or industry – not K-12 education. If you did, perhaps you thought about psychoeducational diagnostic work more generally, or early literacy and numeracy screeners more specifically. However, you were probably not thinking about statistically derived classifications of learners. You might be surprised, then, that there is a class of statistical models called cognitive diagnosis models or diagnostic classification models (DCMs) that are used in educational and psychological applications to bridge various branches of applied cognitive psychology and modern measurement.

In simple terms, DCMs are statistical models that classify learners along a variety of dimensions – known casually as attributes – in order to provide relatively fine-grained profiles of skill mastery for each student. Conceptually, they can be used in any discipline with assessments that are designed to measure these attributes reliably. Whether the resulting classifications of learners provide any “added value” in pedagogical or clinical terms hinges upon the assessment design more than anything else.

Motivations for My Reflections on Diagnostic Classification Models for K-12 Education

There are two main reasons why DCMs are on my mind at the moment. We recently passed the 12-year mark of the publication of the book Diagnostic Measurement: Theory, Methods, and Applications, which I had the great fortune of writing with my colleagues Jonathan Templin and Robert Henson. Our goal at the time was to translate the relatively opaque psychometric literature that is commonly only read by psychometricians, data analysts, or statisticians, into more accessible descriptions. The book included descriptions of what these models are able to do in applied settings and how one would specify, estimate, and interpret different models within a unified framework as an applied analyst. Given the ensuant statistical advances in the field, I was curious about which parts of our original walkthrough stood the test of time and which parts were predictably updated by current research.

The current state of the field is of particular interest to me since we have recently gotten inquiries at the Center about the promise and limitations of these models in different contexts where arguments about “innovation” are valued and foregrounded. It was interesting to see how technical research with this class of models had progressed along the initially charted pathways more than 20 years ago and how we are now at a time where some of these models are actually applied for operational reporting in large-scale contexts.

Two of the most powerful operational applications of DCMs that I am currently aware of are the Navvy Education system developed by Dr. Laine Bradshaw and colleagues, now a part of Pearson, and the Dynamic Learning Maps system developed by Dr. Neal Kingston and colleagues. There are of course examples of targeted use cases for research purposes in many technical papers, but I am talking about actual operational applications where classifications from these models are used for reporting and decision-making at scale.

In this blog post, I want to briefly recap some of the fundamental considerations around these models. As with the original book, I am again thinking of more applied colleagues with a technical background in state or local education agencies, as well as vendors and other consulting organizations for instance.

I have created an extended walkthrough of the issues I revisit in this blog in an accompanying primer that is written in a frequently-asked-questions format (Rupp, 2023). I treat that document as a living document and will update it periodically as fundamental new understandings about these models arise. In the remainder of this post, I conduct a short run-through of the key characteristics of these models – my “greatest hits” of questions that I have gotten over the course of my career so far.

Perspectives Matter When Addressing Questions about Diagnostic Classification Models

I have found one of the most powerful drivers in conversation around DCMs to be the foundational values, perspectives, and associated expectations that the stakeholders in that conversation bring to the table. Let me illustrate this observation through two contrasting perspectives.

On one end of the spectrum, there are applied stakeholders who seek truly “meaningful” reports on their target population, by which they often mean that assessment results are interpretable, actionable, and impactful within the targeted use contexts. For these colleagues, including those working in education, one of the powerful promises of DCMs is that they are designed to provide something akin to a clinical or medical diagnosis. Put differently, one of the main hopes under this perspective is that there is new, deeper, and/or more complex meaning that can be derived from assessment scores than had these models not been used for data analysis.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are the technical experts who view these models as tools within a broader psychometric and statistical toolbox. For these colleagues, it is important to understand what these models are technically capable of under the right kinds of conditions and how the mathematical and statistical connections they share with other frameworks can be leveraged in practice for the specification, calibration, and criticism of these models. That is, these colleagues are interested in how these models can be used to provide technically “trustworthy” classification patterns.

Both of these perspectives are helpful in certain moments during the development of assessment systems and, ideally, can come together in the end in successful applications. Importantly, bridging the two ends of the spectrum requires a systemic view of assessment design, implementation, and evaluation.

At the end of this post is a compact overview of a variety of fundamental considerations around these models. Specifically, I provide three illustrative considerations for four foundational aspects of work around these models, expressed in question-and-answer format in both more applied and more technical terms. For more extended descriptions, please see the extended compendium document I mentioned earlier.

Concluding Thoughts on Diagnostic Classification Models for K-12 Education

If you read through the considerations / FAQs and think. “Aren’t these mostly the same issues that we have in many other large-scale assessment contexts?” then you are absolutely right! As always, principled assessment design and systemic considerations around implementation supports are paramount for ensuring that results from assessments are both “meaningful” and “trustworthy”. The particular flavor that DCMs infuse into this work does have some unique aspects, but it is generally most helpful to leverage best practices around principled assessment design and build upon them, rather than to conceptualize DCM-based assessment as something that is unlike anything else that came before it.

I would love to hear from you about additional examples of large-scale operational applications of these models or resources that you have found useful in educating others about these models. Please reach out via email and let’s continue the conversation!

Overview of Considerations around DCMs

Aspect 1 – Model Advantages

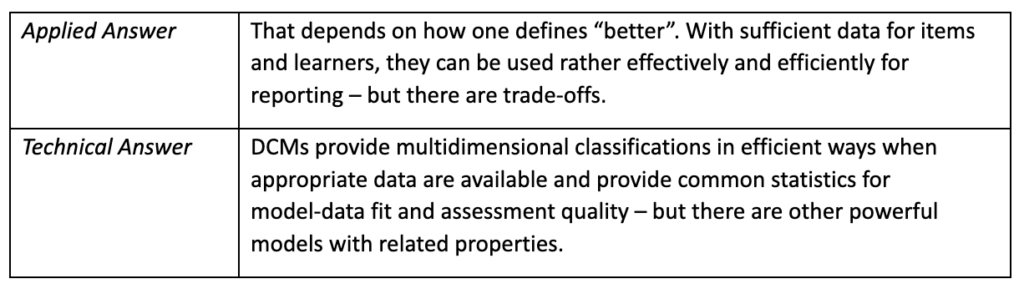

1.1 Are these models better than other models?

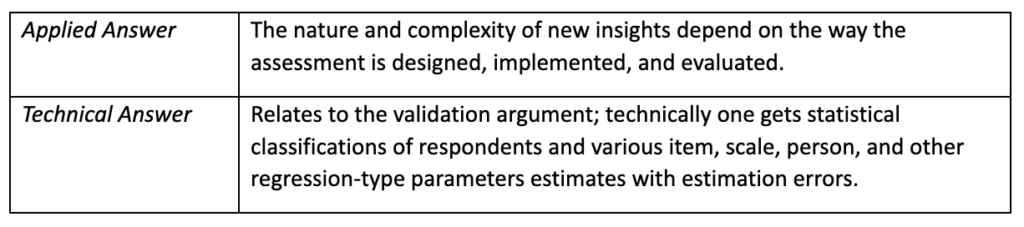

1.2 What insights can I get from these models?

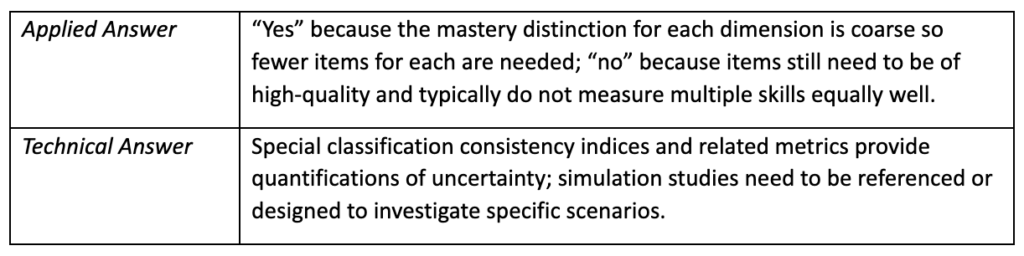

1.3 Can I extract more information from fewer items with these models?

Aspect 2 – Use of Cognitive Information

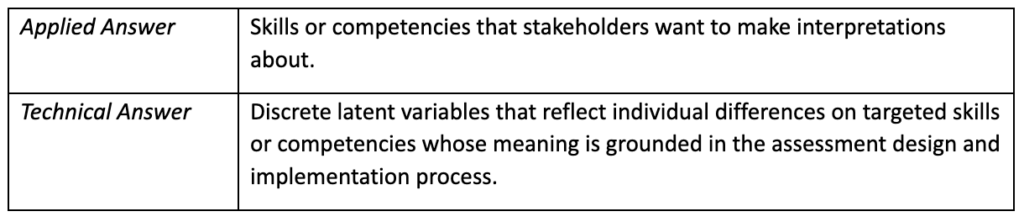

2.1 What exactly are the “attributes” that these models use?

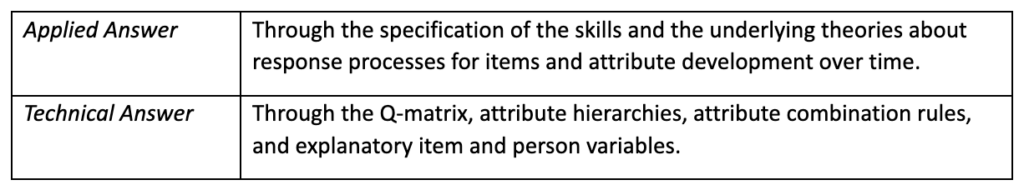

2.2 How does cognitive information get used in these models?

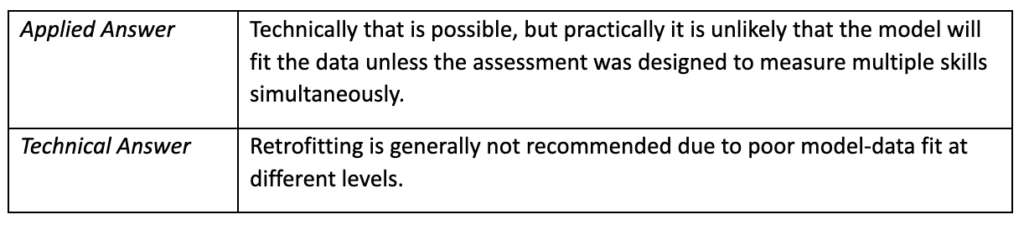

2.3 Can I apply these models to assessments that I already have?

Aspect 3 – Relationships Between Models

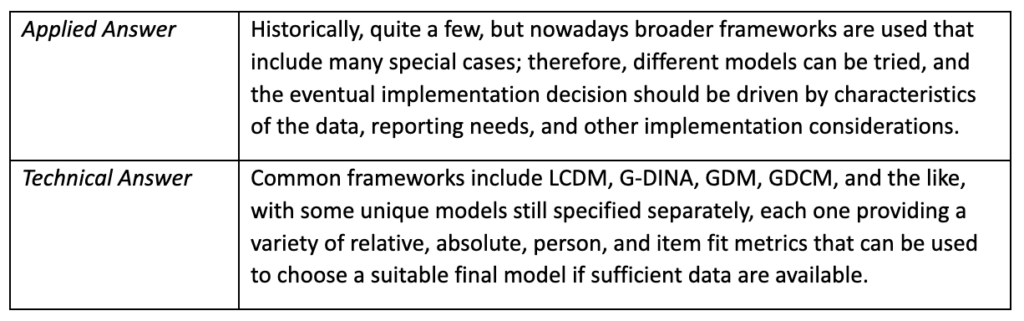

3.1 How many distinct models are there, and which model should I choose?

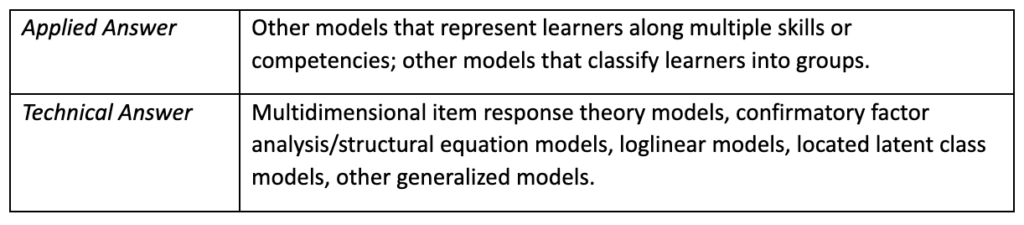

3.2 What other modeling families/frameworks are these similar to?

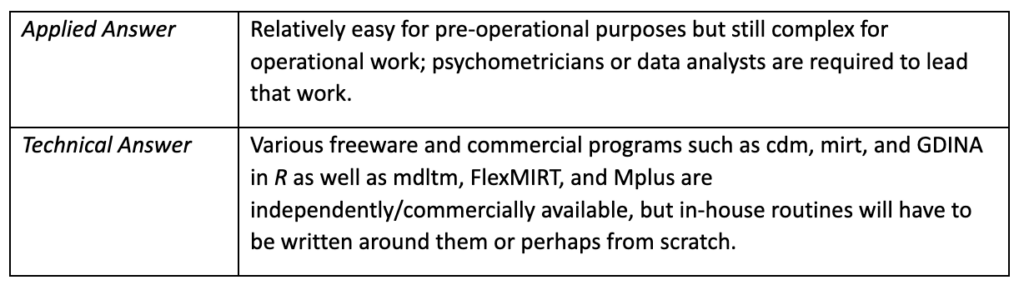

3.3 How easy is it to run these models on data?

Aspect 4 – Advanced Applications

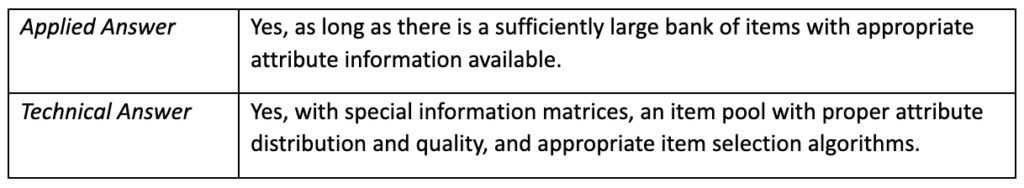

4.1 Can I implement adaptive testing designs with these models?

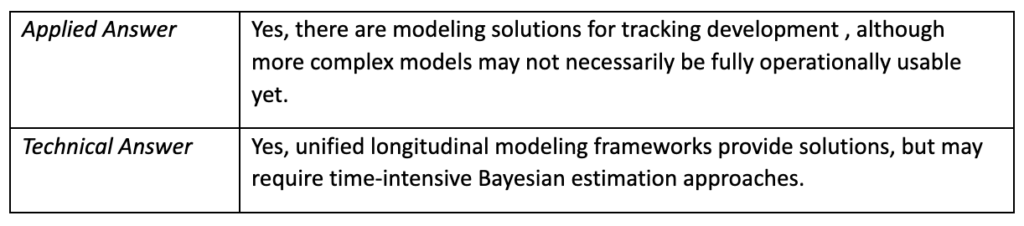

4.2 Can I use these models to track the development of learners over time?

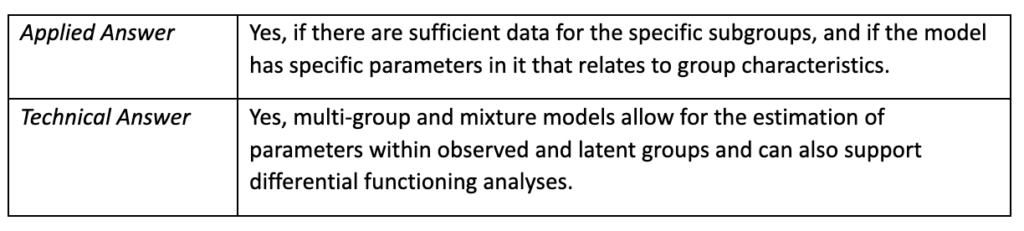

4.3 Can we estimate profiles for different subgroups of learners?

Selected Additional Resources

All of the following resources are most useful for colleagues who have at least a basic understanding of how one models data from assessments with common statistical models.

Bradshaw, L. (2016). Diagnostic classification models. In A. A. Rupp & J. P. Leighton (2016). Handbook of cognition and assessment: Frameworks, methodologies, and applications (pp. 297-327). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ma, W., & de la Torre, J. (2019). Digital Module 05: Diagnostic Measurement – The G-DINA Framework. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 38(2), 114-115.

Ravand, H., & Baghaei, P. (2019). Diagnostic classification models: Recent developments, practical issues, and prospects. International Journal of Testing, 19, 1-33.

Rupp, A. A. (2023). Primer on diagnostic classification models. Dover, NH: Center for Assessment.

Rupp, A. A., Templin, J., & Henson, R. H. (2012). Diagnostic measurement: Theory, methods, and applications. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

von Davier, M., & Lee, Y.-S. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of diagnostic classification models: Models and model extensions, applications, and software packages. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.