How We Talk About Results of Assessment and Accountability Systems

States Can Use Results to Support Schools, and Crisis Communications Principles Can Help

For states, testing season is ramping up, and that means results will once again trigger rounds of blame, applause, or something in between. If states plan to do what U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona suggested—use assessment results helpfully as flashlights, not hammers—they need to get out in front on messaging now. Lessons from crisis communications can help support schools and improve the usefulness of accountability systems. In this post, I offer principles for planning strategy, execution and outreach.

I first heard the flashlight metaphor from my colleague Damian Betebenner in the mid-2000s when I oversaw assessment, accountability, research, and evaluation in West Virginia. I’ve always remembered it because it conjures a constructive vision for assessment data (especially when coupled with growth) and can help inform the next better question, rather than being used to punish or label (although it’s not lost on me that we’ve been shining flashlights for some time).

I applaud the constructive, insight-building power of assessment data, and was gratified to hear Cardona frame it that way. Using assessment this way is especially important right now, as millions of students—and their schools—are trying to rebound from the pandemic. That’s why it’s crucial to start planning that messaging now, long before spring test results are released.

Using Crisis Communications Principles to Talk About Accountability

In communicating about assessment and accountability systems, we often use common principles that help us land our message: We try to connect with ideas that are meaningful to our audience, for instance, and we try to make our message clear and accessible. When reporting these results, crisis communication principles are particularly relevant.

I’m not saying that reporting results is a crisis, but as we exit the COVID era, it can often feel like a crisis, since it sparks new rounds of upset about students and ramps up the pressure on states to make things better. One of the fundamental principles of crisis communication is to prepare before the crisis occurs.

In our work with states, we advise them to plan (and plan, and plan again) to account for the pressure and the need for fast decision-making. Below, I offer several ideas that are grounded in crisis communication strategies. I will describe each one, and close with some practical advice on a process states can use now as they prepare for their assessment administration season, recognizing that reporting results is just around the corner.

Principle 1: It’s a Marathon, Not a Sprint.

You’ve probably heard this maxim. It applies to many things, including reporting assessment and accountability scores.

If you think about the amount of time that it takes to prepare for running a marathon, you’ll recognize that you need to start your training way in advance (no marathons planned for me…). You must consider your exercise, diet, recovery, mobility, and maintenance approach. How many miles do you need to increase over time? How much is too much or not enough? How much time do you have before the actual race? Preparation requires a series of calculated decisions, each with its own strategy and planning.

Think about communicating assessment and accountability results yearly: a lot of planning goes into it. From test development through reporting results, it takes time, effort, science, and involvement from every layer of the educational system. We make that investment, with its costs and trade-offs, to get a look into how our education systems (at the macro-level, not necessarily at the student level) are doing: where schools are making progress or stagnating, and where we need to invest more resources and support. Are there any large groups of students we need to serve more effectively? With all that we invest in it, large-scale assessment should be a tool to improve our education systems, not a way to justify some policy, pet project, or funding stream, or to scold schools or educators.

Principle 2: Plan Before It Happens.

To frame assessment and accountability results well, states need to define three things in advance: (1) the content, (2) the target audience, and (3) the delivery strategy. While these determinations seem straightforward, each one is nuanced. Below I explore each of these ideas and offer some activities and questions to help with the framing.

Defining the Content

States need to define and communicate the value proposition. Why do these results matter? States need to figure out how to communicate why these results matter, and convey that message to inform, not persuade. Additionally, they will need to figure out what the public and their constituents might be upset about and be prepared to say, simply and honestly, what they’re doing to address those concerns.

Defining the Target Audience

States should ask: Who are we trying to reach with our assessment and accountability results? Who are the key users and consumers of our message? It’ll be important to meet those consumers where they are, which will require understanding, for each target audience, what anchors their beliefs.

Recognizing that prior perceptions influence future actions—and that those anchors make it difficult to change perceptions—states will need to envision outreach as an opportunity to educate, not to persuade. They must do all of this with sufficient empathy to avoid alienating vulnerable groups of people.

Of their key audiences, which ones are best situated to amplify their messages? Can they use those audiences or advocates to amplify their messages? States can create efficiencies in their communications by identifying amplifiers and meeting them where they are. The messaging must be consistent and persistent, however, to ensure the final audience doesn’t hear a very different message than states intend.

Defining the Delivery Strategy

The delivery strategy is all about executing the plan. We often hear the phrase, “act fast and act early” in crises, but doing so requires a lot of slow and deliberate planning. While many crises are predictable, such as large-scale assessment and accountability reporting, others are not. Pre-assigning responsibilities can help with both and are important to support the delivery strategy.

Another critical action for states is to design the distribution strategy based on the medium of the message. What’s the distribution plan? How should it differ among print, visual media, social media, broadcast media, and word of mouth? Each of these platforms requires different tactics. While crises are unavoidable, having a solid set of processes can help states be more nimble and strategic in their communication responses.

Principle 3: Build a Communication Plan Step by Step.

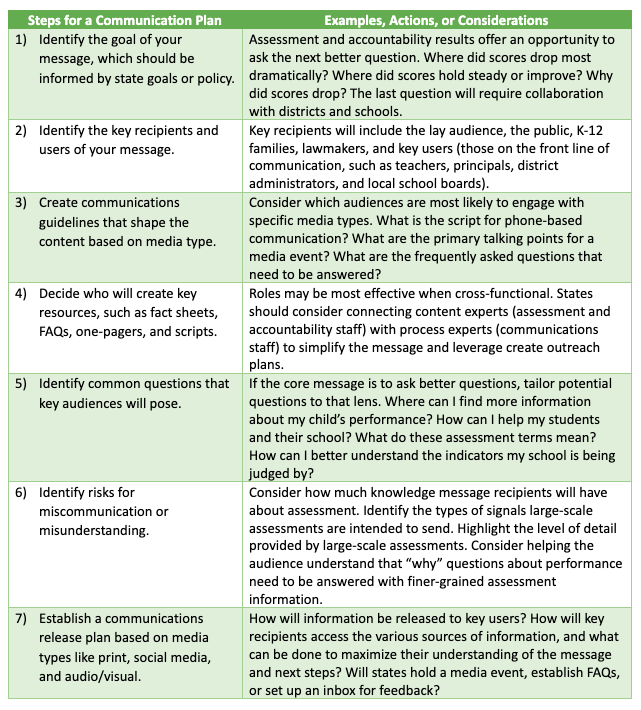

So what does all this mean? In this section, I distill the above considerations into a more digestible series of steps. I propose the following seven steps to develop a high-leverage process for a crisis communication strategy, and I use one example to illustrate them. In this example, a state has just reviewed the results from the most recent spring assessment administration, and scores have dropped after last year’s minor post-COVID bounce-back.

Even with advance planning and a good process, states might still struggle to build the public understanding needed for a shared inquiry into improving student learning. Paying particular attention to what your audiences don’t know can help. Here are two specific questions and a few recommendations to think about as you craft your messages:

What are some big-picture threats to understanding assessment and accountability results?

- Recognize that people are likely to conflate inequality in outcomes and systemic inequalities, such as diminished access or inconsistent opportunities to learn.

- Understand that many people are anchored in a magic bullet theory: “We just haven’t found the right solution yet….”

- Recall that we should not oversell the precision of accountability and large-scale assessment or overpromise their utility in isolation.

What are some ways to approach smaller-picture threats to understanding assessment and accountability results?

- Recognize that many people don’t understand what content standards are.

- Have a brief, effective explanation of school accountability ready for staff members to use.

- Describe how assessment results can be used not to replace teachers’ judgments, but to corroborate their observations.

- Recognize the ongoing conflation between assessment and accountability and describe each clearly and separately.