Using Formative and Large-Scale Assessment as Part of a Comprehensive Recovery System

Educational Assessments to Monitor and Support Student Learning

In a continuation of my thoughts from a blog post I wrote last year, this post provides greater detail about the role of formative and large-scale assessment in student learning recovery. Rather than continuing to obsess about the effects of remote versus in-person learning, assessment professionals should help state and district leaders use assessments to monitor and even improve the rates of learning recovery.

I agree that it’s important to understand the depth of the impact that students experienced, but we can do this without the distraction of highly politicized analyses of students’ varied exposure to remote or in-person instruction. Given all the studies into the effects of COVID-related disruptions, we’ve developed a pretty good understanding of just how bad things were. It’s time to use our knowledge and skills to help move the educational system forward.

Using Large-Scale Assessment to Monitor Learning Recovery

While statewide tests are not helpful for guiding day-to-day instruction, they can be very useful for monitoring large-scale educational trends over time. We at the Center, and others, have been using state assessment results to shed light on the effects of the pandemic on student learning. These aggregate-level results can guide policymaking, at the state and district levels far better than can the results from classroom tests.

My colleague Damian Betebenner uses the metaphor of an automobile dashboard to help our partners understand key aspects of monitoring student performance. The speedometer provides an indication of learning velocity, which we can use to see if learning is accelerating or decelerating. The odometer describes how much learning has occurred (how far we’ve traveled).

We need both the speedometer and odometer to let educators know how quickly students are catching up, how far they have traveled, how far they need to travel to catch up, and how long it might take them to get there. In the assessment world, this means we need both point-in-time measures, such as achievement designations on end-of-year tests, and measures of progress over time (student growth).

Growth measures—the speedometer—are critical because techniques such as student growth percentiles (SGP) can inform educators and leaders how quickly students must learn in order to “catch up” to or exceed 2019 levels. Growth measures can provide a reality check on unrealistic expectations of progress.

Education leaders and other stakeholders might expect students to be fully “caught up” by the end of the 2023-2024 school year. We can save the debate about what “caught up” actually means for another day. For now, let’s assume it means returning to achievement at levels similar to those of same-age students in 2018-19. If that’s the case, then SGPs, pegged to a 2018-2019 baseline, can help educators understand whether the amount of progress students need to make is typical, exemplary, or somewhere in between. For students to be “caught up” by the end of 2024, for example, could require acceleration experienced by very few students historically, suggesting that such ambitious goals won’t be realized unless some very different learning and teaching approaches are employed.

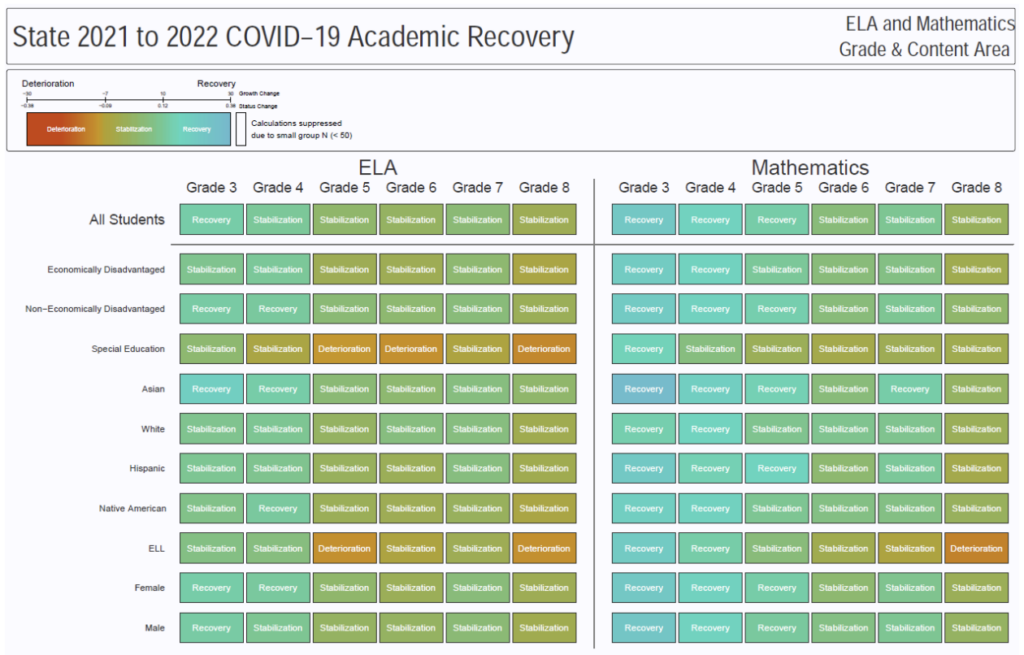

Damian has translated these kinds of complex calculations into data visualizations that convey a tremendous amount of information to state education leaders and policymakers. In the following display, users can see for each grade, content area, and student group whether student learning is starting to recover, remaining stable, or continuing to deteriorate. These labels are associated with aggregate SGPs benchmarked against pre-pandemic rates of learning so that “stabilization,” for instance, describes student growth at rates typical of pre-pandemic times. Stabilization is not fast enough to catch up, but it is better than continuing to deteriorate.

These sorts of analyses, displays, and metaphors help education leaders understand the degree to which they are helping students address their interrupted learning. This work also highlights a key value proposition of state assessments.

Using Formative Assessment to Support Instruction and Student Learning

I just described the powerful role that large-scale assessments can play in monitoring educational progress over time. But like we and others have noted for many years, state assessments are not designed to support day-to-day instruction of individual students. For this, we must turn to formative and other assessments closer to the classroom.

Guest blogger and formative assessment expert Caroline Wylie offered three suggestions for how state leaders can support increasing the quality and frequency of formative assessment in their schools:

- Publicly sharing examples of high-quality formative assessment practices,

- Providing extended and sustained professional learning opportunities, and

- Adopting policies and practices that support—rather than hinder—the implementation of formative assessment, such as developing equitable grading practices.

My colleague Carla Evans then described five conditions that can either support or hinder the use of formative assessment to accelerate student learning. These include:

- Teacher knowledge

- High-quality curriculum and other instructional materials

- Local policies related to curriculum pacing and grading

- School structures that support educator collaboration and extra instructional time

- Leadership support and integration with teacher evaluation and supervision

As you can see from Carla’s list, assessment, on its own, regardless of whether it’s formative or not, is not a silver bullet for fostering learning recovery for students. In fact, early in the pandemic, when we naïvely thought all students would be back in school in the fall of 2020, we wrote that school districts needed to focus on ensuring that all students have access to high-quality instructional materials before worrying about specific assessment strategies/choices.

High-quality curriculum provides a framework for designing assessments to support learning, such as formative probes, daily homework or related assignments, and end-of-unit assessments. Curriculum-embedded assessments also provide a framework for interpretation so educators can better understand students’ performance and make the necessary adjustments to ensure student learning is progressing and even accelerating.

At least four of Carla’s recommendations overlap with Caroline’s points. Taken together, both writers offer a roadmap for state and district leaders to implement formative and large-scale assessment approaches that can support accelerating student learning.

Moving Ahead to Monitor and Support Learning Recovery

Assessment professionals would be wise to spend their time focusing on how we can use our expertise and tools to help monitor and support learning recovery instead of trying to figure out exactly how much ground was lost or just how bad remote learning was for many (but not all) students. Formative assessment can help support learning recovery, but we need large-scale assessment to help us evaluate whether learning is, in fact, accelerating.

It could be helpful to understand what worked and what didn’t about remote learning as we reimagine education, but that work cannot distract from the pressing need right now to use assessment effectively to monitor and promote student learning. I’ve provided a few suggestions and examples here, but I know there are other very good ideas. I look forward to seeing many of them in action in the coming years. Students and educators need all the help we can provide.